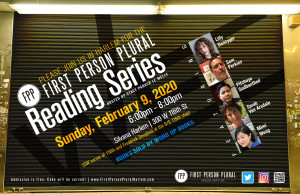

In the FPP Interview with Professor Holly Mastuzo, who is joining us on Sunday from Jacksonville, Florida, we hear about how the natural and built environments inform her work, the historic connection of Harlem and Jacksonville, her ambivalence about land ownership, the glory of “women helping women” and so much more. Come to Silvana on Sunday, April 28th to hear Masturzo read with Chaya Bhuvaneswar, Jericho Brown, Veronica Liu, Willie Perdomo, and Alexandra Watson. Admission is free. See you at 6pm!

In the FPP Interview with Professor Holly Mastuzo, who is joining us on Sunday from Jacksonville, Florida, we hear about how the natural and built environments inform her work, the historic connection of Harlem and Jacksonville, her ambivalence about land ownership, the glory of “women helping women” and so much more. Come to Silvana on Sunday, April 28th to hear Masturzo read with Chaya Bhuvaneswar, Jericho Brown, Veronica Liu, Willie Perdomo, and Alexandra Watson. Admission is free. See you at 6pm!

You are a writer and professor of humanities and women’s studies born in Frankfurt, Germany, raised in Tampa, Florida, and now living in Jacksonville. Could you share a bit of how Florida’s natural and built environments have informed your art and teaching? Because Florida is so flat, we have a long horizon. Growing up on the Gulf side of Florida, the water also is calmer than on the Atlantic side. I remember many family trips to the beach, or boating from my aunt’s old property near Weeki Wachee Springs out to the Gulf, and how we could wade for what seemed like miles out from shore with the sea barely rising above our waists. There is a sense in a landscape like that not only of calm but of the possible, a slow, easy possible that can continue for as long as you are willing to open to it.

The Florida sky on morning in Neptune Beach.

Of course there also are intense tropical storms and hurricanes one learns to size-up and shelter against, and no shortage of insects and other natural hazards. Harriet Beecher Stowe writing from Florida for readers up north, encouraged visitors not to expect only the paradise they may have heard about but to learn to appreciate “the wrong side of the tapestry” (Palmetto Leaves, 1873, p. 26). I love that scratchy, intense side of Florida, too, the heat and persistence of insects, and how all the green that surrounds us has an edge made for hard living.

It feels impossible not to pay attention in wild Florida and that quality of presence is something I seek out in most spaces, whether that be on the page or in the classroom or traveling to other places in the world.

Blue Springs, FL where the manatees often gather in large numbers.

How do you find Florida’s human history impacting your thinking and your work? I believe if more people in the U.S. knew about the early chapters of Florida history, it could serve as an expansive counterpoint to some of our cultural tensions. Even in 2019, Florida has had more years under Spanish-speaking rule than English-speaking ones.

The two areas of Florida I know best, Tampa (Old Port Tampa and Ybor City) and Jacksonville-St.Augustine have layers of cosmopolitan ethnic histories that challenge and complicate the black-white narratives of Southern history as well as the immigrant-native-settler narratives of colonial history.

The cigar factories of Ybor City and the mixed Cuban, Italian, and somewhat smaller in number Jewish immigrants created significant radical political cultures in the decades before and after 1900. Growing up I spent a lot of time after school in central Ybor and the traces of that were still noticeable. In St.Augustine, not far beyond the walls of the Castillo de San Marcos, Fort Mose functioned as the first free black settlement in what is now the United States. While many of those residents followed the Spanish to Cuba when the British took possession of Florida briefly from 1763-1783, some returned during Spain’s second rule which continued until 1821. Their strategic yet comprehensive acceptance of free black peoples in north Florida rewrites the one-dimensional story of the Southeast with which we are often presented. It has taken going away and coming back to Florida as an adult for me to appreciate how formative growing up in and near those cosmopolitan cultural histories have been and I am working on engaging that more directly in this next phase of my writing.

It also has been good to spend a good portion of my last decade teaching a course called Humanities of the Americas where talking about these earlier urban spaces in Florida with students reminds me of the potential of these chapters in history to positively impact how we think about ourselves and where we live.

Atlantic Beach, FL and the long, walk-able horizon.

Which natural landscapes inspire you? How do you feel about cities? If you could be living and working anywhere, where would it be? I am definitely a coastal girl and am most drawn to small to mid-size coastal cities that I can take in on a long day’s walk. Tampa Bay will always be a special place for me, visually, spiritually, physically. Visiting Salerno, Italy for the first time last summer, the nearest city to where my great grandparents immigrated from, brought a recognition of landscape, scale, and place as well. I feel similarly in San Diego, a semi-tropical climate, an open bay, feeding into a mid-size city.

In a perfect world, I would divide my time living and working between small apartments in St. Petersburg, FL and a community on the western coast of Italy. I have a lot of ambivalence about home ownership or land ownership, so I am often listening in to what it can mean to “settle” somewhere. As clear as I am about landscape, I’m not there yet in terms of residence.

Walking has long been a part of your creative process. Tell us more about this. Even as a young girl, I would go outside with my notebook. I remember sitting under azalea bushes as a kind of sacred imaginative act – there is a short poem that appears in the first little notebook I have even about azaleas. To some degree it is about finding a place of true privacy, not only to go inward without interruption, although certainly that plays into it, but to be able to connect outward in a more sacred way than I often feel I can do in domestic and professional spaces.

In college, the walking became pitched, sometimes to extremes as I processed grief. Yet during these years, too, I learned how to journal more intentionally and I began to notice how intertwined the early part of my writing process, the germination and early drafting, was with my physical experiences, both in terms of walking, dancing, and physiologically, particularly with my menstrual cycle.

As I’ve lived with that awareness more, and traveled with it more, the walking as personal practice and as creative practice is as much about being in this human-sized, human-shaped form on the largeness of the earth. Along the way to any vista there are surprises, messages and interruptions outside of myself that help me hear and see what I am thinking and wanting to share. Often I’ll pause at a halfway point on a long walk, sit in some make-shift spot, and journal. Then as I turn to walk back to where I live, I begin reworking by memory parts of what I wrote in order to listen to what surfaces, what sticks and stays, what starts to turn or is too thin to hold.

I believe in the neuroscience of walking as a creative practice, too, to engage the whole body as a writing instrument, to be the whole person, and not to compress the spine and truncate the nervous system by sitting down. And then there are the gifts of the sky and the sun.

Sometimes there is a stronger element, too, of female liberation. Long walks are a way of exercising freedom and not being available to, or resisting, the social order and the domestic expectations of contemporary life. The history of the limitations on women walking is well documented in Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust, and more recently Flâneuse by Lauren Elkin. I think my walking is less flânerie as it is less about being seen; I am not presenting myself as an urban, visible walker, and I usually am not consuming culture either.

Tell us about your current or recent writing. The material I will be reading from at First Person Plural has a working title of Simple Medicines. It is work I began last summer at cultural studies seminars in Rome on the Italian Diaspora, and then found the central vocabulary and metaphors for the project when I traveled immediately following those seminars to Salerno to visit what remains of the botanical gardens of the historic Salerno Medical School. I will return to southern Italy this summer, in Calabria, for a short series of writing workshops punctuated with anthropological visits and look forward to layering an even more southern Italian context to the material.

On the academic side, it has been good this last year to have collaborated with two other scholars to produce a special issue of the journal Feminist Teacher exploring dimensions of performance and pedagogy. My own scholarly writing currently is focused on the ethics of participatory art and the possibility and limitations of cultural healing in public performances such as the AIDS Memorial Quilt, Ruth Sergel’s art action Chalk that commemorates the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, and Anna Halprin’s Planetary Dances.

What has Harlem meant to you? When do you remember first knowing of Harlem? Teaching in Jacksonville – and it is increasingly important to me to say I do not live in Jacksonville, the word, the history of that name and Andrew Jackson’s role in the Indian removals bring me pain whenever I have to write it – but the cultural highway between Jacksonville and Harlem had its significant moment in the early part of the 20th century. James Weldon Johnson wrote “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” in Jacksonville (where he was born) for an event in 1900 at Stanton High School which still offer classes under the same name. Norman Studios launched a notable number of silent black films before Hollywood was established as a film center, and then Zora Neale Hurston spent different spells of time in Jacksonville. Many of the films produced by Norman Studios featured all-black casts appearing in positive, non-stereotypical roles, including the film The Flying Ace based the life of Bessie Coleman. There are pockets in present-day Jacksonville where this cultural connection is remembered, yet many where it is not. Perhaps Harlem probably doesn’t think much about Jacksonville these days, but there is a continuum running up and down I-95 for us to tap into when we want to remember it.

It’s 2019. What gives you hope? What gives you pause? Hope is not a word that feels close I’m afraid. I don’t feel despairing or pessimistic, but I feel firmly in a period of short term, or maybe seasonal is a more poetic way to put it, approach to understanding the world. Hope feels bigger than I dare imagine lately.

Where I have found moments of hope are in quiet exchanges between women where I feel or experience one or more of us going deeper in our energy reserves to help each other out even as it seems there is little left to give. When I was hiking up the hillside into San Cipriano Picentino last summer (the town the Masturzos are from), and near the edge of what one of my ankles could bear, a middle-aged woman stopped in her citron green hatchback to give me a ride the last few minutes of the way. “Le donne aiutano le donne,” I managed to say, correctly I think. Women help women. And she squealed with delight and squeezed my knee. It was so simple and perhaps others experience that kind of human kindness in a thousand different ways, but I am noticing it most often now between women and perhaps noticing our tiredness as much as the stretching to reach each other.

Saying that I also want to say I appreciate the real, quality conversations with my father (and my mother), but elsewhere in my small circle of living, whether it is my generation, my place of work, my location, there seems to be a real absence of presence of men leaning in to the shared work of our greatest challenges. Sometimes I can hold space for what I hope must be happening below the surface for them, yet I’m not seeing the effort of what some would call the shadow work necessary for us to lift the lid off of the cultural habits that hold us back. I like to think that is happening elsewhere and I simply haven’t witnessed the best of the transformation work I know people are doing in the world and with themselves.

What American crises keep you up at night? Honestly what I spend the most mental energy trying to unlock lately is what I might call a crisis of discourse, of critical thinking and wise speaking from that thought. The mental and narrative frames (and visual, too) we often use to communicate with each other seem incomplete to allow us to listen fully and to discover what community spaces we most need next. I think also about what acts of convening, how to gather and regather people so that we can genuinely unlock the patterns that have limited us and oppressed many, and then let those patterns go. Perhaps those crises are human and not only American, yet I do think about them in particularly American forms.

Is there a piece of writing– yours or someone else’s–that really speaks to your experiences these days? Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas, specifically the poems “Whereas” and “38” that precedes it in the volume. There is an attentive teaching in those poems to me, a carefulness of reading and of critique, as well as an exacting presence and immediacy to seeing and seeing through the complexity of our history now. She has spoken about her care in naming and witnessing historical violences, truthfully without nostalgia, and I find great teaching in her work on the particularity of her subject and also the approach more broadly.

What should the future be? Easier.

Easier for others. I am not sure that it will be. We often get in the way of helping ourselves.

When do you feel most “we”? When do you feel most “I”? The most meaningful “we” experiences I have had were during contact improvisations or related group improvisational dance work. What makes these experiences possible is usually they are led into with deep personal movement practice, a coming into awareness of the body-self-world beingness of that time gathering together. The “we” becomes more available when each participating “I” has taken the time and space to clear their intentions, align with the group purpose, and show up fully. It was extremely potent being in group improv on the outdoor deck at Anna Halprin’s Mountain Studio in San Rafael, California. By the end of the week, in an unrehearsed improv, I shared a powerful moment of both movement and sounding with a Barcelona-based Maori performer that felt to me at least to channel the pain of land displacement across continents. It was almost to powerful to stay with and I know only could come through because of the quality of the field, the site where we were and the intentions she and I both brought to that week. Our overlap found each other and amplified, and then was supported and witnessed by others which moved it beyond either the personal or the arts friendship we shared.

Dancing with Tamar (and Peter) on the Mountain Home Studio deck during a Tamalpa Institute workshop with Anna Halprin.

Dance is the place where it happens most readily I think. Perhaps theater and it’s collaboration broadly, but I think dance even more so because it is less verbal. I think too of dance making after Women’s March with friend and colleague Rebecca Levy, who teaches at the college where I work and is the Artistic Director of Jacksonville Dance Theatre where it is a joy to serve on the Board. We actually did not set out to create a dance about Women’s March, but the walking and protest movements showed up in the movement phrases she, then I, and then the students we worked with brought to the choreographic improv sessions that happened just following the first Women’s March. We all just kept saying “yes” and there we were by the end with a “March of the Snowflakes.” By the time that dance arrive to tech rehearsal, the (male) tech manager, too, was joining in with the performative rule-breaking that dance became about and he suggested the ending needed a confetti canon. Perhaps not a dance that will be remembered in the history of choreography, but it was a wonderful dance of that cultural moment the audience responded to viscerally and positively – a great reminder of what happens when an unknown “we” begins to drive and the “I” gets out of the way.

Dancing with Tamar (and Peter) on the Mountain Home Studio deck during a Tamalpa Institute workshop with Anna Halprin.

Do you have any trouble with “we”? Sure, I definitely struggle with “we.” It can be extremely frustrating and disappointing to begin to enter what seems like a “we” project to then find oneself tangling with a cobweb of “I” energies. The “I” still leads in most arenas, even when we think we are inviting the “we” in. A couple summers ago I was part of a hosting team for an event designed to engage artists, activists and community developers around the concept of “creating collective healing spaces.” The idea was to offer a deep dive workshop to co-teach from different areas of expertise devoted to calling people together to work on cultural issues and group tensions. Wow. Some great threads emerged yet it was also a heavy ego ride for many involved. When I check myself, I think I resist the “we” most when I sense (correctly or not) the purpose of the “we” has been disrupted or needs to be renegotiated. That is part of why I am so interested the ethics of participatory art. I haven’t figured out how to invite as fully as I’d like the shape of projects that are more centered in the “we” and I hope I can do that in the second half of my life. I know it’s where some of the most surprising and transformative creating can happen.

Who are writers that we should be reading right now? Layli Long Soldier I mentioned earlier and recommend highly. I also am reading in conversation the works of Richard Blanco, Natasha Tretheway, and Tracy K. Smith. What’s helpful to me is to listening to them and between their voices for the bicultural realities that are and are emerging around us, and which are instructive to name.

For academics looking to rethink the university, I recommend reading The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy by Maggie Berg and Barbara K.Seeber, and anything on decolonizing the university. I’m finding the small volume A Third University Is Possible by la paperson (K. Wayne Yang) particularly helpful to carry around as an antidote to the forces of the academy.

What advice would you give emerging writers today? Honor your “No.”

Believe in your own timeline. We can push ourselves and use discernment when not to push or not to push in a traditional pattern. There can be a kind of press and chase dynamic that conferences and contests and residency applications – job applications – create for emerging writers and this dynamic can start to feel all-encompassing. It is OK to step out of that especially if you are stepping into your own path. I also think it’s helpful to actively value other mediums as sources of insight on process and form.

Is there something I didn’t ask you that you’d like to share? Coming into the reading, I am thinking about the tension I sometimes am aware of between the written and spoken word, the embodied poem and the printed poem. It is a gift leaning into that tension in a specific way, and I think I will always feel it, not uncomfortably but it does seem never to resolve itself.

The Fellows of the 2018 Italian Diaspora Summer Seminars at Universitá Roma Tre with The Calandra Institute (CUNY) as featured in a local Roman newspaper.

Photos by Holly Masturzo.

“I believe that art and literature fundamentally become better when we allow for different visions and voices to be seen and heard,” says writer Mimi Wong when considering the power of diversity in publishing. In Wong’s FPP Interview, we hear about how working in various media has impacted her writing, the toll rejection takes, guidance for emerging writers, and much more. Read her words then hear Wong read live with Lilly Dancyger, Sam Perkins, Pitchaya Sudbanthad, and Sarah Van Arsdale this Sunday at Silvana from 6-8pm. Silvana is located at 300 W. 116th St near Frederick Douglass Blvd. Books sold by Word Up! Books. Admission is free. Please RSVP via Eventbrite here. – SPL

“I believe that art and literature fundamentally become better when we allow for different visions and voices to be seen and heard,” says writer Mimi Wong when considering the power of diversity in publishing. In Wong’s FPP Interview, we hear about how working in various media has impacted her writing, the toll rejection takes, guidance for emerging writers, and much more. Read her words then hear Wong read live with Lilly Dancyger, Sam Perkins, Pitchaya Sudbanthad, and Sarah Van Arsdale this Sunday at Silvana from 6-8pm. Silvana is located at 300 W. 116th St near Frederick Douglass Blvd. Books sold by Word Up! Books. Admission is free. Please RSVP via Eventbrite here. – SPL